Battle of the metaphors

stochastic parrots v magic understanding v spatial explorers

Over the weekend, the news breaks of a new class action lawsuit in the foundation model training space, this one against StabilityAI, DeviantArt and Midjourney. Read more about it here. The complaint is here. Let’s talk about this more next week. (I edited the below slightly for clarity post-publication, on the morning of 17 Jan.)

And in other news… Even as Microsoft seems ready to bring (un)OpenAI models further into the mainstream via a rumored US$10b investment, regulators are starting to move on the foundation models specifically: China has announced its Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis Internet Information Services, and news broke that the EU will be relooking the entire framework of its 2021 proposal for an Artificial Intelligence Act in light of the new issues raised by generative AI. Well, I’m not sure if that second development qualifies as “moving”, but still…

There is a huge challenge coming as policy-makers and judges will try to assimilate the technology to case law and jurisprudence, precedents and principles. Making legal decisions about technology will require working with metaphors.

So what are the metaphors, the abstractions, the shortcuts, that best describe the foundation models? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each metaphor? And what are the stakes involved in choosing between them. Trying to work through all this is proving a much larger task than I imagined, but here is an initial survey.

Metaphor One: LLMs are stochastic parrots that understand nothing

This metaphor comes from a famous paper by linguist Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru and others, the paper that is said to have gotten Gebru fired from Google, ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜’. The paper, not very complimentary to parrots, brings together a number of arguments for why we should reassess the race to scale in making Foundation Models, and take greater cognizance of the issues and problems with these models, including the scientific weaknesses in this approach. The paper also mentions the dubious legal status of the ever-larger training sets.

At base, the metaphor that drives this paper is based on a straightforward, humanist argument.

“As Bender and Koller argue from a theoretical perspective, languages are systems of signs, i.e. pairings of form and meaning. But the training data for LMs is only form; they do not have access to meaning. Therefore, claims about model abilities must be carefully characterized.”1

Bender and Gebru see the achievement of GPT-3 et al as a manipulation of the form of language alone. The failure is in the tests that are meant to show understanding, but which GPT-3 has managed to cheat:

“If a large LM, endowed with hundreds of billions of parameters and trained on a very large dataset, can manipulate linguistic form well enough to cheat its way through tests meant to require language understanding, have we learned anything of value about how to build machine language understanding or have we been led down the garden path?”2

Given the philosophical starting point, this concern is hard to dismiss. Moreover, the authors move from this to point to a very real, specific danger with the LLMs. The danger stems from the fact that humans look for coherence in utterance. We actively read meaning into what we hear or read in a dialogue, as part of an effort of cognitive empathy that is at the heart of interpersonal communication. The stochastic parrots are spitting out formally meaningless text, but we, as readers, are creating meaning in them.

Metaphor Two: The models learn, they understand, like humans

We should expect this sort of metaphor to be pretty deeply embedded in the field of AI, since the architecture of neural networks is meant to mimic the human brain. Neural networks were first designed in order to try and understand something about the human brain, and it’s worth remembering that they are really quite different in design from the input to fixed output architecture we most often think of when we think of computer processing.

Some AI scientists argue convincingly that AI research has helped us understand better how the human brain processes information, how we think. (Take for example Terry Sejnowski and Yann LeCun in the excellent episode #111 of the Eye of A.I podcast.) So neural network researchers make use of metaphors back and forth between computers and humans all the time. It’s built in to the field. Anthropomorphism is a feature, not a bug.

But as a rhetorical move it is also exactly what Bender, Gebru et al were warning about. We want to ascribe meaning into language behavior, and there is a strong desire to anthropomorphize stochastic parrots. Anyone who has spent time with Chat-GPT will understand this. (And see this disturbing, fascinating article, “How it feels to have your mind hacked by an AI”, from Blake on lesswrong.com.) So it’s useful, but dangerous, especially when you move away from the specialist world of computational neuroscience and neural network design and use the terminology more loosely.

It seems to me that AI business people use this way of describing AI partly both as a kind of technical shorthand they have learned from the scientists, but also as a way to hype them up. And while using words like “attention”, and “acquiring new concepts” to explain aspects of the models seems really useful within the technical literature, they are also susceptible to misuse, when used way outside their original scope.

As an example, look at the way one of my favorite AI researchers on Twitter prolific Twitter shitposters, Roon, who knows better for sure, doubled down on this metaphor in an article written for a general public with commentator Noah Smith, former economics professor and Bloomberg columnist.

“At training time, they study a vast corpora of text scraped from the internet, and gain an intelligence as broad in scope as the source material itself.”

Emad Mostaque, founder of Stability.ai, is very consistent in his use of language that portrays Stable Diffusion as having learned concepts, able to understand what different objects are, able to understand the style of a particular artist. In his trademark telegraphic style he explains the (admittedly hard to explain) extreme compression of the Stable Diffusion model by saying “it took 100,000 gigabytes of images, two billion images, and created [a] two gigabyte file that learned from the principles of all those images.” He has been known to double down on this, and explain that the foundation models give us a completely new capability in AI, of understanding concepts:

“Our human brain is made up of two parts. There’s the recall part and there’s the principle based part. And what we were missing in AI was the principle based approach. We had lots of “if this, then that” statements. But this is something fundamentally different. This is again, mimicking the human brain to be able to do things like understand academic papers, to do things like often drug discovery and things, but in a very different context and milieu to that which came before.”

(The above from the transcript of his interview on the Infinite Loops podcast, or see also his interview with Kevin Roose and Casey Newton for The New York Times).

Anyone who has seen an image appear in Stable Diffusion, from an app on their iPhone or PC, in response to the text one typed in as a prompt, knows how tempting it is to believe that the model “understands” or “recognizes” many ideas, ideas of landscape, portraits, particular objects and people, ideas of style, visual effects, how a photograph taken with a 23mm lense looks different than one taken with a telephoto lens, and so on. And then when you understand that this power is compacted into little more than two GB needed for the model, of course the idea of “understanding” becomes attractive. Understanding is how we humans generalize from a small set of principles and ideal types to solve a huge number of problems. Surely something similar is going on here?

I’m going to have to hold that thought for now, as I’m still struggling to understand a bit better the way Stable Diffusion works, and the CLIP models for understanding (oops!) comparing word-image pairings that is a key part of its training. More exploration of this question to come.

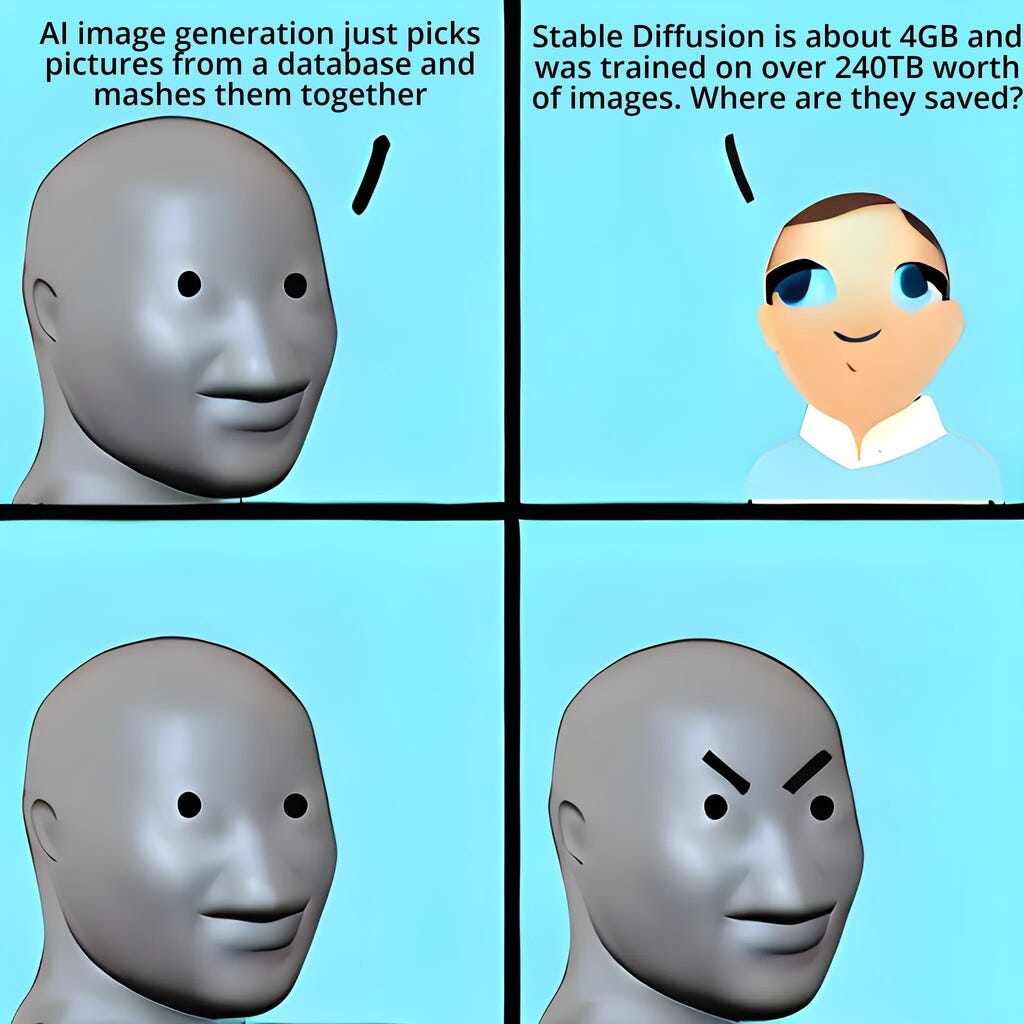

But I will say that the naive criticism that Stable Diffusion is just “mashing up images that it has copied” drives Stable Diffusers crazy, and I think for good reason. The way Stable Diffusion manages to combine the CLIP model with a general-purpose model for turning visual noise into pictures really is quite far beyond a mashup.

Metaphor Three: A space of possibilities

To express the statistical relationships between words in LLMs (and in Stable Diffusion) we use vectors, measurements of the closeness or distance of different words (tokens) from each other (in different settings). The math to create these measurements works by simplifying and grouping the relationships, trying to represent them in the most economical way, compressing the amount of data needed into a smaller “latent” space.

So the most attractive metaphor, to me, for using the models, is that you are exploring that multi-dimensional space of relationships inside the model. Here’s Kevin Kelly of Wired magazine rhapsodizing on how this works:

“[the new digital art] lives in a possibility space as large as painting and drawing—as huge as human imagination. But you move through the space like a photographer, hunting for discoveries. Tweaking your prompts, you may arrive at a spot no one has visited before, so you explore this area slowly, taking snapshots as you step through. The territory might be a subject, or a mood, or a style, and it might be worth returning to. The art is in the craft of finding a new area and setting yourself up there, exercising good taste and the keen eye of curation in what you capture. When photography first appeared, it seemed as if all the photographer had to do was push the button. Likewise, it seems that all a person has to do for a glorious AI image is push the button. In both cases, you get an image. But to get a great one—a truly artistic one—well, that’s another matter.”

Kelly sees this latent space being as large as the human imagination.

An alternative view would be that put forward by artist SVLT. This from a thread that was widely shared in November 2022, do explore that by clicking on the Twitter post below.

“Any image made by ml (machine learning) cannot originate from beyond that latent space (whose shape is predetermined by training examples).…An analogy would be that machine learning is like a train. it can take you to places people have already been, but it cannot come off the rails. a human is free to roam wherever it may choose to.“

But those artists and commentators who seized on svlt’s explanation (and the many more simplified versions out there) are at risk of underestimating the creativity that can come from exploring the million-dimensional space created by the words associated with images on the internet. That “train” of art, and even just the train of (copyrighted! copied without permission!) art posted on the internet, has taken us to a lot of places, and a friction-free exploration of all the multiple dimensions of that inbetween can indeed be a very interesting synthetic sort of creativity (as well as generating nightmares, but we’ll leave that topic for a future post).

Parrots, explorers, those who understand & those who don’t

The “explorers of latent space” metaphor is probably most useful of the three, as long as we resist inflating that space to the sum total of human creativity as per Kelly. It brings us closer to a more nuanced understanding of how models are creative and powerful and derivative of the data they were trained on.

What I can say for sure is that the naive use of the “computers understand” metaphor by tech company lawyers and policymakers is a cop-out. It often shows up in the form “computers read by copying”, which devalues the idea of reading quite a bit! Copyright is meant to protect human expression. We need to work harder on understanding how these models work, not just rush to adopt them.

Emily M. Bender et al., ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜’, in Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’21: 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event Canada: ACM, 2021), 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

ibid, p. 616