AI in the IPA

and thoughts on the creation-generation spectrum - November 11, 2022

Your correspondent is a little distracted, attending the International Publishers Association Congress in Jakarta, Indonesia, with sideline meetings of the ASEAN Publishers Association, and catching up with so many comrades. So I’ll confine this week’s update to a few points, and try to have another issue of the newsletter next week after the Asia Pacific Copyright Association annual meeting, hosted by NUS Law School. AI and IP feature in a number of papers there, so stay tuned.

AI has come up a few times at the Congress, but mostly at a very high level of generality. The exception was Jessica Sänger’s intervention on day one. For those of you who don’t know her, Jessica is Director, International Affairs of the German Publishers and Booksellers Association, and Chair of the IPA’s Copyright Committee. (I serve with Jessica on the Copyright Working Group that feeds in to that Committee’s discussions.) At least two of her interventions on the dedicated AI panel struck me as very useful.

Data and the communication right

First, she raised an interesting question about the TDM exceptions under which some copying of training data has been done. These exceptions often do not include a communication right. For example, the UK exception 29A(2)a says

“Where a copy of a work has been made under this section, copyright in the work is infringed if the copy is transferred to any other person, except where the transfer is authorised by the copyright owner…”.

The corpora used to train LLMs are often posted online, for downloading and checking of various kinds. They are routinely communicated by the machine learning community, and this would seem on the face of it to therefore not be covered under the exception. Another question would be whether the models themselves communicate the material copied, in their routine operation.

Can AI output be copyrighted?

And Jessica set out her position that the output of AI content generation should not be awarded copyright protection, given that it is not the product of human creativity. She wondered what would happen if we we fill the creative space with not-so-good AI rewrites of past creativity.

I haven’t deeply engaged with this question, not when the legal status of AI inputs seems so urgent. My own view is that the human work (and volition) involved in content generation is still significant (my fledgling attempts at writing image prompts feel like work!) even if it is a curiously opaque task, coaxing desired results out of the solution space of a foundation model.

Secondly, I do see plenty of human creativity being applied to the works that come from content generators: that is the creativity that went into the works that form the training data and which have been remixed. I see them as subsidiary works (just subsidiary of a large number of originals).

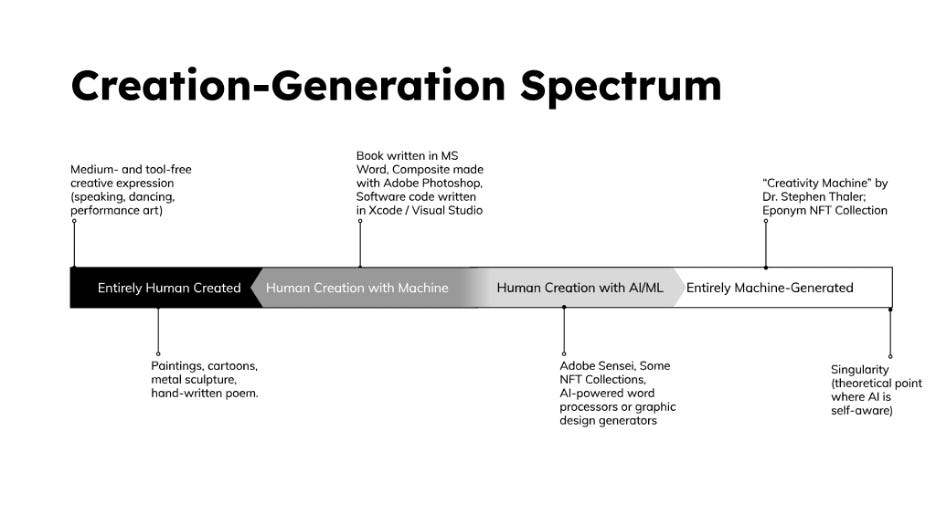

Interestingly enough, the US Copyright Office, which does register copyright, has been grappling with this quite a bit recently, a debate I hadn’t tracked. See this article in IPWatchdog. It seems the USCO is trying to find a point on the “creation-generation spectrum” where there is enough human creativity to merit protection. (Not sure if the “creation-generation” spectrum idea comes from Graves or elsewhere, but it is useful, and I reproduce Graves’ diagram below.1

(diagram credit: Franklin Graves)

There’s more from Graves for IPWatchdog from a related pro bono test case brought by The Artificial Inventor Project, represented by Dr Ryan Abbot.

Developments, new products, and etc

When the machine generates content, it can generate content very quickly. Here’s a new tool (DreamSpace.art) that leverages that speed. I’m putting this first because the embedded video gives you a sense of how an image generator works. It’s about exploring the “prompt space”, the new obsession of those using these new tools.

There’s already an AI Film Festival, in San Francisco. That didn’t take long.

It’s too hard to keep track of all the new generative content tools being launched (literally over night), so let me just point you to a Twitter thread that covers a lot of them. Don’t be left behind!

We also need to understand more about Stephen Thaler’s “creativity machine” to understand the space on the right side of the spectrum.