transforming what exactly?

or how the author of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili gets name-checked in the US Supreme Court

I’m trying not to be prisoner of the headlines, but there are so many of them!

We should start off with the US Supreme Court decision in the case of Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc v. Lynn Goldsmith et al. The judges found against the Foundation, saying that its licensing of a print based on Goldsmith’s photograph to Vanity Fair magazine was not fair use (especially considering the artist had already licensed the underlying photograph from photographer Goldsmith, but under different terms). This case is not about AI training. But the question of the transformative nature of a work, traditionally considered as part of the first factor in fair use—the focus of the Supremes’ ruling—will be very important in any eventual decision on AI training without permission. This question is, as per Judge Leval, the “soul” of fair use. Adam Liptak’s report in the New York Times is a good summary of the judgements and dissent but really I would recommend at least a good skim of the judgement itself.

So what are the implications of the ruling? The key decision point for the court is that the transformation most at stake here is not in the message or form of any work copied. It is transformation in the “purpose and character” of the works created by the copying. The majority focuses on the transformation in the use of the work. And Large Language Models have many purposes, but they are being used (by humans) to create, to write, to generate text. Works have been copied so that the users of the tools can create more works. I think the picture is even more clear with the image generators. Of course LLMs embody enable a near infinitude of transformations of the works they copied without permission (except when they just repeat them, see last newsletters…), but the purpose and character of the works created as their output is not changed.

Of course we are talking about tools that can be used for so many purposes… but then similarly multipurpose are an author’s skills at manipulating language!

Justice Elena Kagan dissents on precisely this point, and is joined by Justice Roberts. They argue that that transformations of form and content are more important than transformations of use or purpose, and Kagan complains about this narrowing of perspective: “Because the artist had such a commercial purpose, all the creativity in the world could not save him.”

Kagan mobilizes art history in her dissent to explain to us why this shouldn’t be the case… defending Warhol’s creativity in transforming the Goldsmith photographs, and decrying “the majority’s lack of appreciation for the way his works differ in both aesthetics and message from the original templates”. All artists make use of what came before… and so on.

[para edited 21 May] I am more sympathetic to the comments of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in a prior hearing of the case, “The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,” Judge Gerard E. Lynch wrote for the panel. “That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.” But here am I, an accredited art critic (member of the Singapore chapter of AICA, the International Association of Art Critics), writing about legal points!

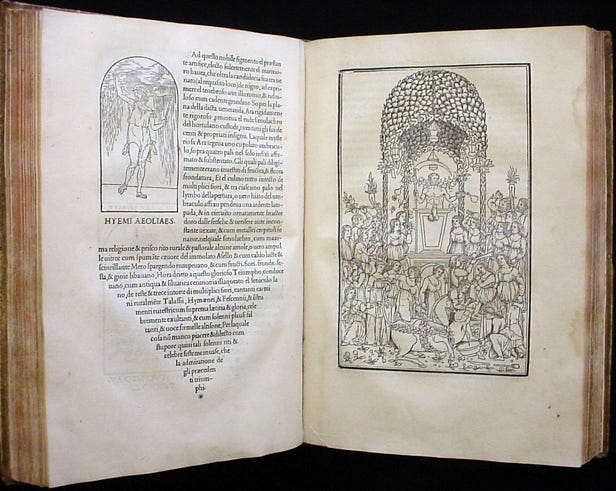

And in fact Judge Kagan seems very art historically well-informed, and well suited to aesthetic judgement (the benefits of a good Princeton liberal education?) Her dissent is fun to read! The judgement is richly illustrated in full colour, with examples of photographs, magazine covers and Warhol’s artwork, but also reproductions of Giorgione, Manet, Velásquez, El Greco, Francis Bacon. Even my old favourite the Dominican monk Francesco Colonna makes his way into the footnotes. But surely Kagan understands the dangers of seeking to mobilize such domains in cases of law?

It is indeed hard to predict how judges will bring together their assessment of the four factors (and the multiple components within the first factor) in any given case. And the eventual AI training data case is going to have many different complex elements to its narrative and its arguments, the interpretation of any one of which could send the judgement spiralling off in a different direction.

There are many many reasons a court will be tempted to agree with Google and Microsoft that AI training on copied (and illicitly copied) works is fair use. We can expect AI creators to hammer on the fact that the copiers created from their copying “something new and important”: a “highly creative and innovative” software platform (that is quoted from the judgement in favour of Google’s copying of code in Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 U. S.). They will remind us that the entire purpose of copyright is, as described in the US Constitution, “to promote the progress of science and useful arts”.

LLMs are surely an advancement in computer science (although maybe not as huge as Sam Altman told the Senate Judiciary Committee they were) but they are also now creating a huge transfer of economic value from those copied to those doing the copying. “Why look up a website when ChatGPT can give you the answer?”

Yes, did I mention Sam Altman’s testimony to Congress…? “Such an irony seeing a posture about the concern of harms by people who are rapidly releasing into commercial use the system responsible for those very harms” Sarah Myers West, managing director of AI Now Institute, quoted in the New York Times. That’s one take.

Others see this as OpenAI’s attempt to “kick away the ladder” and “ensure OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, et al. remain in complete control with the most powerful models and protect themselves against any competitors with an ironclad and regulated monopoly.” In the most extreme view, all on the path to “a true WEF wet dream of public-private partnerships in lockstep, which is nothing other than the old gods of communism rising again”.

Mr Altman “please regulate us” stance got a pass for many reasons, including that his company is seen as an asset in the one endeavour that truly unites American legislators, evidentially much more important than preventing the country from defaulting, and that’s oneupmanship on being tough on China.

The Chinese are creating A.I. that “reinforce the core values of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese system,” said Chris Coons, Democrat of Delaware. “And I’m concerned about how we promote A.I. that reinforces and strengthens open markets, open societies and democracy.”

This statement hints at the ways the AI debate is getting entangled with the rhetoric on China in the US at the moment. This is not likely to be a healthy thing. Though I’m as capable as the next (liberal) person of making snide remarks about Chinese regulations insisting that the output of LLMs uphold core socialist values, there is a lot more going on in China’s draft regulations, and it is probably worth diving into that in more detail. Future newsletter!